Sustainability and Toys

(a rant and an essay)

In an age when we should be focusing on the environment and our impact on the environment, and thinking about ways to curb our dependence on non-sustainable resources, like oil, we are buying, to borrow a phrase from Nanci Griffith, unnecessary plastic-like objects. Ms. Griffith made her comment during a nostalgic moment in England while introducing her song “Dancing at the Five and Dime,” but I am reminded of the phrase every time I wander through the local Kroger. Happy Meals, grocery store checkout lines, and guilt have changed our toy buying habits over the last 50 years. No longer are toy purchases limited to special occasions and holidays. Now they come standard with children’s meals, as premiums for filling up at the local gas station, and as giveaways in the bottom of cereal boxes. As a toy store owner, I find myself wondering how many barrels of oil we could have saved by foregoing the toy in the Happy Meal.

The term de jour these days is “environmental footprint,” or rather how much impact do we have on the environment based on the choices we make about products and services. Most people, myself included, don’t stop in the middle of the big box aisle and wonder where the raw materials for a product originated, how far the materials were shipped to be manufactured into something else, and how far they were shipped to reach the particular aisle I’m standing in. The distance the raw materials traveled is a key component of the product’s environmental footprint.

I come from a long line of modelers and woodworkers. My grandfathers both had wood shops where they disappeared to listen to baseball games on the radio and “made stuff.” My parents “made stuff” as well– miniatures, architectural model, tools out of Sears washing machine motors. Toys, when I was a kid, were made in their workshops and woodshops: wooden trains and trucks, blocks from two by fours, marionettes from scrap wood. Inventive toys. My friends had plastic toys from Mattel, I had a dollhouse from my mother’s workbench, built out of scrap lumber and bristol board and complete with towel carpeted floors and stenciled walls and doors that worked. I used it as a space port…the result of watching Lost in Space and Star Trek as a kid. In the summers, I would follow my Grandfather Dorsett to his woodshop and make boats out of scrap wood to float down the irrigation ditch that marked the west side of their yard. We made stilts out of two by twos and two by fours, stilts that probably wouldn’t pass current safety standards. We would pour over the old issues of Popular Mechanics on our Grandfather’s shelves, looking for projects and ideas for the pile of scrap lumber in the workshop. Nearly every member of my generation of the family learned how to “make stuff,” it was a right of passage during our childhoods. The environmental footprints were small. Lumber came from lumber yards that carried wood from local mills. Nails were purchased by the handful, by the pound, and carried home in brown paper bags. When toys broke, which they are prone to do with use, we simply glued them back together and went on about our business.

As I was recently reminded, we haven’t lost the ability to make stuff; we voluntarily gave it up for the sake of convenience. We buy what is cheap and what is quick and what frees up our time to do other things that seem so much more important. As a rule, we don’t go to our workshops and our garages to make stuff. We buy plastic objects, wrapped in plastic, advertised on television, and sold in big box stores. We buy toys someone else has defined as educational–computer games and learning systems, talking products that ask our kids to mimic information rather than build something from their imaginations. And in the long run, we lose. Rather than buying toys from companies that harvest local woods, we buy plastic. Rather than buying wood from a local lumber company and creating a toy, we buy plastic. Rather than creating a sock monkey or purchasing fabric dolls and puppets, we buy plastic. Rather than building models from paper and wood, we buy plastic. And the plastic toys, by definition, have enormous footprints. The distance between Iran and China is approximately 3,000 miles as the crow flies (considerably more if you figure out the shipping routes for oil tankers). The distance between China and Washington D.C. is 7,300 miles. That amounts to a bit over 10,000 miles from oil well to manufacturing site to shelf space at Tyson’s Corner.

In the mid-1930s and during World War II, when resources were in short supply and often restricted, many of the toys were made of wood and cardboard. Models of the planes of war, including those of Wallis Rigby, were printed on cardstock . After the war, the paper models that required little more than a hobby knife and some white glue disappeared, replaced by plastic models. Raggedy Anne was replaced with Barbie. Please don’t get me wrong. My favorite toys, as a kid, were an etch-a-sketch and a set of lego blocks, made entirely of plastic and heaven knows what else. But in an age when decreasing petroleum supplies and rising prices have caused most of us to reconsider our habits, we don’t stop to think about the impact our choices of toys may have.

The next time you go into a store, stop and ask a clerk or an attendant “where did this product come from?” Ask “how was it made?” Ask “who made it?” Ask “did they use local materials?” Sustainability starts with the choices, choices about materials, choices about footprints, and choices, finally, about the memories left after the toys have long since disappeared or have been passed on to the next generation of kids.

Meghan H. Dorsett, AICP

Publisher, Dorsett Publications

The Scale Cabinetmaker

The Community Planner

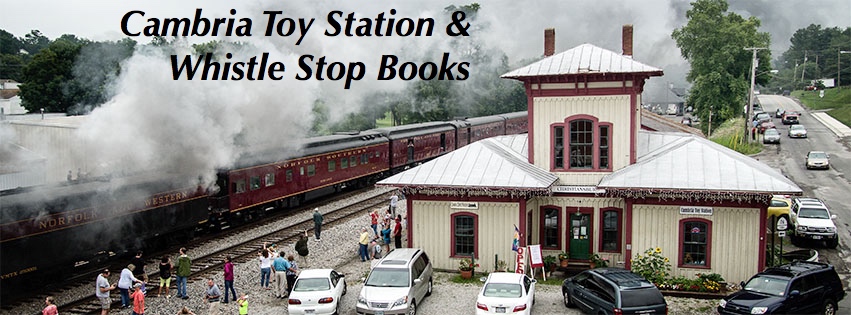

Co-Proprietor, Cambria Toy Station